by

Caitlin Kinser

| Jul 24, 2024

History of Olympic Rugby — Rugby 15s

One of the greatest developments in modern Olympics was the creation of the International Olympic Committees’ (IOC’s) Olympic Agenda 2020, which sought to safeguard Olympic values and strengthen the role of sport in modern society. In essence, this agenda permitted host countries’ organizing committees to propose new sports for the Games they would be hosting. The primary purpose of this agenda was to prioritize innovation, youth engagement, and gender balance. In recent years, this has been successfully implemented, with sports like surfing, skateboarding, karate, baseball, softball and sport climbing debuting or reemerging at the 2020 Summer Olympics held in Tokyo, Japan, in 2021.

Alternatively, some sports may be removed from the Olympics due to disinterest or lack of appropriate global governing body; for example, sports like baseball and softball were previously removed from the Summer Games in 2005 due to the belief that those sports were only popular (e.g., competitive) in the Americas and parts of Australia and eastern Asia. Unfortunately, Olympic rugby shares a similar history.

Rugby debuted in the Olympics in the 15-a-side variation of the game in 1900 in Paris. This variation features 15 players on each team competing for possession of the ball through grappling, tracking, rucking, scrummaging, etc., in order to advance it across the pitch (which is 100 m long and up to 70 m wide) across the try line, similar to an end zone in American-style football. These matches last 80 minutes, broken down into two 40-minute halves.

Unlike American-style football, after each tackle, play keeps going, whereby tacklers have a moment to release the ball carrier and roll away, followed by the ball carrier releasing the ball, placing it towards their team and likewise rolling away. Amidst this chaos, arriving players on defense and offense will contest for the ball in a ruck, whereby they will bind to one another and attempt to drive the opposing player off of the ball. In rugby, the ball may only be passed backwards or laterally; however, you may advance the ball forward by running or kicking it.

If any of this sounds confusing to you as a new fan of the sport, you are not alone. For this, and many other reasons such as the lengthy matches, necessary time to recover between matches, and lack of global presence, rugby 15s fell out of the Olympics in 1924.

Modern Olympic Rugby — Rugby 7s

Modern Olympic Rugby — Rugby 7s

Rugby 7s, a variation of rugby 15s which is played on the same-sized pitch but with seven players per side and only seven-minute halves, was presented for inclusion in the 2012 Games, but was not formally accepted as an Olympic sport until the 2016 Olympics.

Rugby 7s has since been a staple of the modern Olympics, joining Paralympic Rugby (which has been included since the 2000 Games), as it is a sport played worldwide, with minimal equipment, and is the only collision sport where men and women play by the same rules. This version of rugby is more easily understood by laypeople, all the while presenting high-speed action and scoring. This upcoming Olympics will be the third consecutive Summer Games with Rugby 7s, giving the impression that rugby 7s is here to stay in modern-day Olympic competition.

American Rugby

Rugby is one of the most rapidly growing collision sports in the United States, and about one-third of registered players are women, which permits increasing opportunities for female athletes to participate at the collegiate level and receive financial support to do so. Currently, there are over four dozen men’s and women’s varsity rugby programs nationwide and countless club-level teams, with women’s rugby programs in particular seeking to grow to 40 varsity programs nationwide in order to achieve NCAA status.

Demands of the Game — Biomechanics of the Scrum

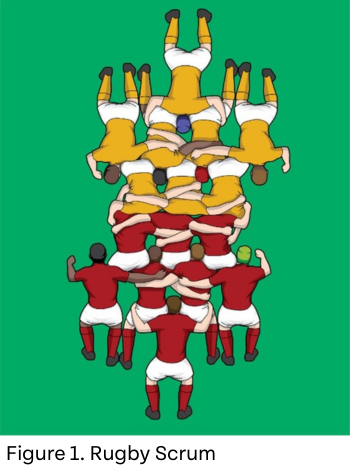

As mentioned above, rugby is a high-velocity and physically demanding sport. One of the hallmarks of physicality in rugby is the scrum. In the 15s variation of the game, the scrum consists of eight players from each team bound to one another (Figure 1) using only their legs and feet to drive over the mark of the scrum to move the ball to the back of the scrum to make it playable by their team.

The strength behind this movement has been featured in promotional content such as Oracle Red Bull Racing, whereby the Bath Rugby Club bound to one another in a scrummaging stance to compete against an F1 car — and the players didn’t give up any ground (Figure 2). In a scrum, the team producing the greatest force, in a controlled manner, will successfully win the scrum, providing tactical advantages in a game. Thus, force production is of great interest for rugby stakeholders.

Within the scrum, one can expect to see a sustained force output of 4-8,000 N for full packs (i.e., eight people) of male players. This force is typically maximized when players are binding at ~40% of their stature with feet parallel to one another and with the knees and hips at an angle of around 120°. Indeed, the maximum force measured during a sustained push of a full pack in laboratory conditions has been shown to be upwards of 16,000 N, which can be normalized to roughly twice their force-to-body-mass ratio. Importantly, these forces are less pronounced in the 7s variation of the game as there is only one row of three players from each team competing for the ball, with the focus in 7s being more on speed, longer runs and more frequent scoring.

Katie Hunzinger, Ph.D., ACSM-CEP, is a biomechanist, clinical exercise physiologist, and assistant professor of exercise science at Thomas Jefferson University. She is a former Division I rugby player and remains involved in rugby as either a consultant, World Rugby Educator, or regional-level rugby referee. Moreover, her research actively recruits rugby players as a means to better understand the mid- to late-life effects of repetitive neurotrauma through collision sports. Dr. Hunzinger’s goal is to make sport inclusive, safe, and sustainable.