Building the Ship as It Sails

2025 ACSM Honor Award Winner Stan Herring, MD, FACSM

I had the pleasure of speaking with 2025 ACSM Honor Award Winner Stan Herring, MD, FACSM, over the course of three Zoom meetings in November 2024. During that period, Stan’s home was without power for a handful of days in the wake of a “bomb cyclone” and concomitant “atmospheric river” that blustered their way into the Seattle area (Stan’s stomping grounds). Stan ventured out to the office anyway to find a working Internet connection so as to meet with me. I lead with that small anecdote as a kind of scene setting — not of any literal place, of course, but of the style of the man.

Joe Sherlock, ACSM copywriter

Stan Herring is from Texas. He may live in Seattle now, but he’s Amarillo born and bred, and you can hear it. Not only in the gentle twang of the voice but the cadence and richness of the Texas idiom.

And there’s an intriguing and quintessentially American backstory to how the Texas Herrings came to be, one that could fill a volume or two on its own. You see, it was Herring’s Russian Jewish grandfather who, fleeing pogroms at the turn of the 20th century, made his way to the Lone Star State, eventually opening a furniture store in Amarillo that would become the family business and feature prominently in the current Herring’s formative experiences.

As is true for many descendants of immigrants from Eastern Europe, “Herring” is not the original family name; Herring doesn’t know what that name was, and he supposes, as was the custom at the time for those who were fleeing, his grandfather must have simply chosen something commonplace or near to hand. There’s plenty a shoal of herring in the Baltic, after all, and perhaps Herring’s ancestor happened by a barrel of them in port while he was making his way off of the Continent. It’s possible, depending on the itinerary of the journey, that the Russian “Сельдь,” (pronounced about midway between “silt” and “sealed”) or Latvian “Siļķe” briefly became the German “Hering” before at last debarking as the English “Herring.”

Despite the blue-water provenance of his surname, the Stanley Alan Herring of our story grew up landlocked in the Panhandle, moving household furnishings at the family store that by then was in the care of his father. And an immediately recognizable family businessman’s realism, humility — and if I may say, soulfulness — seem to have woven their way into Herring’s fundamental manner of being, in no small part due to his father’s regular koans about getting too big for one’s boots.

Consequently, and though he would likewise “make a name for himself,” so to speak, in his field, Herring’s goals for his life do not seem entirely yoked to his on-paper achievements. It’s not possible to explain who Stan Herring is simply by enumerating the things he does and has done.

But he does a lot. His CV is one of those that meet the page criteria for a novella.

At the moment, Herring, a physiatrist primarily interested in head and spine injuries, is:

- Co-medical director of University of Washington (UW) Medicine’s Orthopedic Health and Sports Medicine program (since 2020);

- Zackery Lystedt Sports Concussion Endowed Chair at the same (since 2019);

- Co-founder (2015) and senior medical advisor at UW Medicine’s Sports Institute (since 2018);

- Second opinion medical consultant for the NBA and NBA Players’ Association (since 2017);

- Second medical opinion physician for the NHL and NHL Players’ Association (since 2015);

- Co-medical director of the UW Medicine Sports Concussion Program (since 2009);

- Associate member at the Harborview Injury Prevention and Research Center (since 2014);

- Clinical professor in the UW School of Medicine’s Department of Rehabilitation Medicine (since 1998), Department of Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine (since 1998), and Department of Neurological Surgery (since 2003); and

- Consultant for UW Sports Medicine.

He has been (and this is far from an inclusive list):

- Medical director of UW Medicine Sports, Spine & Orthopedic Health (2011-20);

- Medical director of spine care in UW Medicine’s Departments of Rehabilitation Medicine, Orthopaedics and Sports Medicine, and Neurological Surgery (2005-11);

- Team physician for the Seattle Seahawks (1997-2022);

- Team physician for the Seattle Mariners ( 2006-24);

- Team physician for the San Francisco 49ers (1983-5);

- Concussion consultant for the US Olympic & Paralympic Committee Paris Olympics (2024);

- Consultant for the Seattle Storm (2010-16); and

- Consultant for the San Francisco Giants (1994-5).

A fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine® (ACSM) since 1989, Herring is also a fellow, charter member and past president of the North American Spine Society and a founding member of the Physiatric Association for Sports, Spine and Occupational Rehabilitation; the International Spine Intervention Society; and the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM), among others. Besides being named an ACSM Honor Award winner, Herring also received the ACSM Citation Award in 2004.

Herring’s contributions to ACSM have been immense. According to nominator and fellow Team Physician Consensus Conference (TPCC) contributor, Margot Putukian, MD, FACSM, Herring has given a presentation at every ACSM meeting since 1994, and by her count put forth 156 unique ACSM-affiliated talks, among them the John J. Sutton Lecture in 2007 and the President’s Lecture in 2010. He’s served on the editorial boards of Current Sports Medicine Reports and Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise®. He’s also served as the co-lead of the TPCC since its inception 26 years ago. A partnership among six member organizations, including ACSM, the TPCC meets yearly to discuss, naturally, a selected topic and clinically relevant best practices for team physicians. Each year, this discussion leads to the production and publication of a consensus paper, and these annual offerings have enjoyed wide circulation and utilization among sports medicine training programs and practicing physicians.

Herring’s contributions to ACSM have been immense. According to nominator and fellow Team Physician Consensus Conference (TPCC) contributor, Margot Putukian, MD, FACSM, Herring has given a presentation at every ACSM meeting since 1994, and by her count put forth 156 unique ACSM-affiliated talks, among them the John J. Sutton Lecture in 2007 and the President’s Lecture in 2010. He’s served on the editorial boards of Current Sports Medicine Reports and Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise®. He’s also served as the co-lead of the TPCC since its inception 26 years ago. A partnership among six member organizations, including ACSM, the TPCC meets yearly to discuss, naturally, a selected topic and clinically relevant best practices for team physicians. Each year, this discussion leads to the production and publication of a consensus paper, and these annual offerings have enjoyed wide circulation and utilization among sports medicine training programs and practicing physicians.

As Herring himself puts it: “One thing I am proud of is that now, due to the growth of the field of sports medicine and the development of teaching materials such as the Team Physician Consensus Statements and others, it’s nice to know that physicians from many different disciplines have become qualified to serve as team physicians. I consider that a real win for athletes at all levels of participation.”

Herring has also served on countless ACSM committees, including the Research Review Committee, the Programming Committee, the Continuing Medical Education Committee and the Advanced Team Physician Course Program Planning Committee.

Outside of ACSM, he’s received the American Academy of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation Frank H. Krusen, MD, Lifetime Achievement Award and the David Selby Award for Contributing Greatly to the Art and Science of Spinal Disorder Management through Service to the North American Spine Society, among many other honors.

Sports, Injuries and a Fork in the Path

Herring first earned a BA in biology (1975) from the University of Texas at Austin before proceeding on to the UT Southwestern Medical School in Dallas, earning his MD in 1979. (He notes, with a chuckle, that if you’re born in Texas as member of his family, you’re obligated to attend UT.) But his combined internship and residency brought him to UW’s Department of Rehabilitation up in Seattle, and he was immediately taken with the landscape. He would ultimately make the Puget Sound his home.

However, it was while he was still an undergraduate that Herring first became (unknowingly) involved with ACSM.

However, it was while he was still an undergraduate that Herring first became (unknowingly) involved with ACSM.

Having grown up in Texas, Herring of course played football from a young age, then added in baseball for good measure, though he wasn’t able to stick with either in the long term.

“I wandered through sports with no particular talent but just enough injuries to where I finally had to let that go,” he says.

He eventually took up golf, both playing on the school’s team and working on a course to bring in some money. He also started running. (“It seemed like most of my life I was running from something, so I might as well do it formally.”) But it was actually an undergraduate phys ed class at the UT that really set in motion the later events of Herring’s life.

“Back in those days, believe it or not — this is shocking — you actually had to take physical education your freshman year in college. Don’t I wish those days were back,” Herring says. “But I got hurt, so I was sent to see this fellow by the name of Karl K. Klein.

Klein, an early member of ACSM whose instruments were displayed as veritable relics in ACSM’s former building, was performing biomechanical analyses of research subjects, so as Herring worked through his own rehab, he got to sit in on some foundational research. Things sort of took off from there.

“I started hanging out with him and learning biomechanics from him and learning how to do rehab from him,” Herring says.

Herring eventually became Klein’s assistant, and Klein became Herring’s advisor. In due time, Klein suggested Herring attend medical school. It was a fundamental life choice: Herring was interested in genetics and other basic science, and he might in all likelihood have fashioned a fulfilling career for himself at the bench. But he enjoyed working with people, and he took Klein’s advice, eventually enrolling at the UT Southwest Medical School.

“So, my less than stellar sporting ability ended up with me actually meeting the man who directed my future,” Herring says.

Herring never did shy away from research, though. He is a prolific author, particularly in the study of the spine and of concussion, and as of mid-November 2024 his work has received nearly 11,000 citations, placing him, according to the medical networking site Doximity, in the top 5% of their researchers. He estimates he’s authored or co-authored roughly 130 papers and “fifty-odd textbook chapters and a few books,” as well as a number of consensus statements.

“While I consider myself mostly a clinician, my academic work has at least had some acceptance, particularly the concussion stuff,” Herring says, somewhat downplaying the truth. The humility bug, which appears not infrequently in our conversation, is biting him again.

Herring shared three titles where he was one of the authors as particular examples of his interests and impact:

- “Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 6th International Conference on Concussion in Sport — Amsterdam, October 2022,”

- “Persisting symptoms after concussion: Time for a paradigm shift,” and

- “Persisting symptoms after concussion: Considerations for active treatment.”

The first publication, a consensus statement, comes on the heels of similar statements released at conferences in Berlin and Zurich, which collectively have received more than 100,000 citations. Impactful enough.

But the second publication, a perspective piece, is an intriguing window into Herring’s mind. In the 2022 paper, Herring and his coauthors argue that the term “postconcussion syndrome (PCS),” doesn’t serve purpose and that a more useful framing would be “persisting symptoms after concussion (PSaC).”

The authors’ first target was the word “syndrome,” which they explain “does not really accurately describe those with lingering symptoms after a sports or recreation-related concussion.” That gone, they made another interesting and ultimately revealing decision. They could have easily adopted the phrase “persistent symptoms after concussion” which was already in the medical literature, but instead elected to use the formulation “persisting,” given that “persistent” may imply a permanence to the condition that would be neither necessarily accurate nor psychologically helpful for the patient.

“Persisting” is active: the symptoms are happening now and continuing to happen, but there is no reason to discount a light at the end of the tunnel, whereas “persistent,” with its hard closing consonant, has a permanence to it that seems to say, You’re just gonna have to live with this, buddy. This is at odds with the fact that the majority of athletes with concussion symptoms do get better. In medicine, and most particularly in Herring’s line of work as a physiatrist, the patient’s psychological state is intimately and reciprocally linked with his or her physical condition. That is, why bother adhering to the treatment plan if your concussion symptoms are going to be persistent? But if they’re only persisting for the moment, it might not hurt to stick to the plan and get through this thing. Always respect the brain injury, but offer hope for improvement.

Subtle? Sure. But subtle doesn’t mean small.

Let’s let some others weigh in on Herring’s impact. According to the seven ACSM past presidents who co-wrote one of his Honor Award nomination letters, “He is internationally known for his work and leadership in concussion care and policy. He was the physician champion for the Lystedt Concussion Law in the state of Washington that set the national standard for concussion care in high school and youth sports and was the model for concussion laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.”

The Lystedt Law is named after junior high football player Zackery Lystedt who, in 2006, suffered what initially appeared to be a minor head injury during play and was sidelined for only three downs before heading back onto the field. Lystedt collapsed after the game, experiencing life-threatening and, ultimately, profoundly life-altering brain injuries. The law, passed in 2009, requires that youth players who show signs of a suspected concussion be seen by a licensed health care professional before they can return to play. Its passage, and his work in aiding in the passage of the subsequent laws across the country that followed in its footsteps, are some of Herring’s most prized accomplishments.

“The Lystedt laws — that was a big honor for me,” Herring says, a little later adding: “And by the way, the campaign to pass Lystedt laws in all 50 states and the District of Columbia was announced at the ACSM annual meeting in Seattle in 2009 with Zack and his parents present. ACSM was a partner in our effort to get those laws passed.”

Stay tuned: The laws and the processes that took place to get them passed will also be the topic of Herring’s upcoming Dill lecture at the 2025 ACSM Annual Meeting in Atlanta. While considering what he was going to speak about, it occurred to him that the lecture as an opportunity to discuss a unique nexus of medical knowhow and policy.

“They asked me what I wanted to talk about. And I said, well, you don’t usually legislate health care, and I can talk about why that had to happen and how the laws came to be, as well as the heroism of the Lystedt family and what’s happened since the law has been passed.”

In a letter supporting Herring’s nomination as the 2025 Honor Award winner, six other writers — including ACSM fellows Margot Putukian, W. Ben Kibler, Francis G. O’Conner, Cindy J. Chang, and Constance M. Lebrun — characterized Herring’s contributions to the field’s understanding of concussion thusly:”:

“Over the last decade, Dr Herring has mentored a new generation of leaders in concussion medicine. His experience, guidance and wise counsel are felt well beyond the U.S. Without Dr. Herring’s knowledge, influence, clinical and administrative abilities, the state of the art and practice for this important and serious injury would be much less. His perspective on this issue is probably one of the most extensive and inclusive in this area.”

Four other nominators, all Olympic physiatrists (including ACSM fellows Jonathan Finnoff and Joanne B. Allen) characterize Herring’s impact this way:

“On a personal note, we frequently call upon Dr. Herring as a mentor to help guide us through the challenges we face as sports medicine leaders. Few have the experience and wisdom of Dr. Herring, and our profession benefits from his willingness to selflessly share his time and expertise with us.”

Pro Sports

“Here I am standing on the sideline watching my team win the Super Bowl, and I thought, ‘Well, this is pretty good for a boy from Amarillo who didn’t exactly know what he wanted to do.’”

Stan Herring

After his residency, Herring joined Sports Medicine and Orthopedics Associates in Portola Valley, California, a stone’s throw from Palo Alto. While there, he first served as a team physician for “a high school, two junior colleges, one Division I college and then, eventually, the 49ers.” This meteoric trajectory took place over the course of roughly three years, from 1982 to 1985. But Herring had long volunteered for just about every team physician role that came his way, high school, collegiate or otherwise. And the notion of what a team physician was only just beginning to coalesce.

“It was sort of building the ship as we sailed it,” Herring quips.

As if becoming an NFL team physician wasn’t enough of a life-altering change, he also met his wife during this intense and inflective period. However, the pull of Seattle and the financial landscape in California drew the couple to the Pacific Northwest for the long haul. Herring took on a team physician job with the Washington Huskies and became a clinical assistant professor at the UW School of Medicine. By 1997, he was a team physician for the Seahawks, and by 2006, a team physician for the Mariners, Meanwhile, he continued to rise through the academic and medical ranks.

It’s clear that working with professional athletes means a lot to Herring — he emphasizes being blown away by their “physical literacy,” which is a wonderfully poetic way of considering the role of self-expression in sport — and he sees the deeper purposes of high-level competition as a means of transcending sociopolitical disagreements, among other things. And he further enjoys, as a he puts it, “making difficult, complex decisions in real time with public observation.” He contrasts that with the experience of working in a more traditional clinical setting: “When I go to work in my office, 80,000 people don’t stand up and cheer.”

It’s clear that working with professional athletes means a lot to Herring — he emphasizes being blown away by their “physical literacy,” which is a wonderfully poetic way of considering the role of self-expression in sport — and he sees the deeper purposes of high-level competition as a means of transcending sociopolitical disagreements, among other things. And he further enjoys, as a he puts it, “making difficult, complex decisions in real time with public observation.” He contrasts that with the experience of working in a more traditional clinical setting: “When I go to work in my office, 80,000 people don’t stand up and cheer.”

Yet his deeper philosophical commitments clearly draw him back to the importance of working with the average person.

“My patients will say to me, ‘Dr. Herring, I want you to treat me like you treat the Seahawks,’ and I say, ‘Well, you have it backwards. I treat them like I treat you.’”

Although sometimes he’ll indulge in a wry riposte after the parry:

“I say, ‘Okay, if you want me to treat you like the Seahawks, the first thing you have to do is choose your parents more carefully.’”

And professional sports do have an unparalleled allure. Herring recounts 2014’s memorable Super Bowl XLVIII when the Seahawks beat the Broncos 43-8 in New York. He took part in the subsequent parade, got a photo of himself and Seahawks Head Coach Pete Carroll holding the trophy, and of course got a ring to boot. (Herring in fact has two Super Bowl rings.)

“It’s pretty exciting when you’re standing there on the field and the confetti is coming down, and you go to the Super Bowl party and you go to the White House and meet the president,” Herring says. “That’s pretty cool stuff.”

But sometime later when he was giving a lecture, a member of the audience suggested to Herring that the experience must have been the best day of his life. Herring demurred.

“I said, ‘You know, I didn’t play any downs, just so we’re clear. It was fun, but I would give back my Super Bowl ring in a minute to go back and watch a second-grade soccer game in which either one of our kids was playing.’”

In Closing

I’m compelled to share two more illustrative quotes from Stan. The first is an anecdote about his father that goes a long way to explaining why the younger Herring operates the way he does:

“When I graduated medical school, my father and I were sitting in a restaurant. He said, ‘Today you’re going to be a doctor,’ and I said, ‘Yes, I am.’ He said, ‘You know, we built a lot of houses, furnished a lot of houses for doctors.’ I said, ‘I know we did, because I laid carpet on Saturday and hung drapes and delivered furniture.’ And he looked at me and said, ‘Some of those doctors were kind of arrogant.’ He said, ‘I’m gonna give you a little advice on the day of your graduation.’ I said, “What’s that, Dad?’ And he said, ‘You get to thinking too much about yourself? You just go try to boss around some other man’s dog.’ And he got up and walked out. That was my graduation speech.”

The second is a sort of summation, in his own words, of his life and work:

“As I look at my life now, I think that the gratitude and the service piece seem to be what sustains me. I’m glad I got to go to the Super Bowl as a team physician four times and was able to experience two victories. I got rings. Man, I got hardware, you know? I’m glad I took care of the Mariners, and I’m glad I’ve been the president of all these organizations. But as I look at my career now, I’m in the fourth quarter — or ‘overtime,’ as my wife says — and upon reflection, at the end of the day, the things I think I will really miss the most are seeing my patients in the exam room and lecturing and volunteering at ACSM.”

That would seem to wrap things up neatly, but there’s just a tad bit more to say.

It’s difficult to adequately convey someone’s manner of being in mere text. Mannerisms, sure. And throwing in colorful, illuminating or idiomatic direct quotes, as I’ve just done, can help. But sometimes if you’re very fortunate, an unrefusable insight appears, seemingly from nowhere at all.

In the process of speaking with Stan, a peculiar phrase popped into my head: “Lacking the tools (or the right) to repair the soul, one might seek instead to repair the body.” Herring’s capacity to feel the weight, the very actuality, of the human condition seems greater than most. It shimmers around him, and one is convinced that his heart is touched by the poignancy of, well, being.

That is my best attempt at explaining Stan Herring. I’m not sure what more you could ask for in a physician.

Story by Joe Sherlock

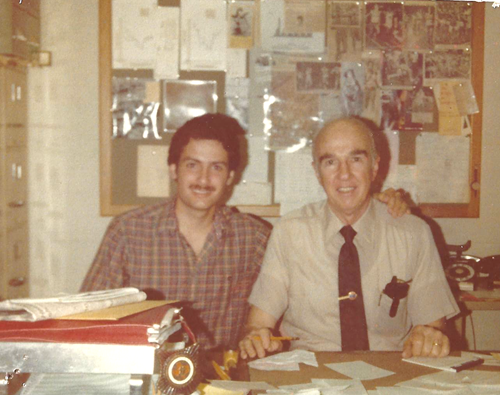

Images courtesy of Stan Herring

Published January 2025