While the health benefits of regular physical activity (PA) are well-documented, its economic advantages often receive less attention. Yet, in a time with rising healthcare expenditures and increasing rates of chronic diseases, PA offers not just a pathway to better health, but a strategy for economic resilience. From reducing direct medical costs, improving workplace productivity and revitalizing communities, the economic case for PA is more compelling than ever.

The High Cost of Physical Inactivity

Physical inactivity is not just a personal health issue but also a national economic burden. The costs of physical inactivity are staggering, with an estimated $192 billion in annual U.S. healthcare spending, accounting for approximately 12.6% of total expenditures. This equates to nearly $2,000 more per inactive adult each year.

The economic toll extends beyond medical bills. Physical inactivity contributes to higher incidence of chronic disease such as heart disease, type 2 diabetes and certain cancers, which drive long term treatment costs. It also reduces workplace productivity and absenteeism, with inactive individuals experiencing higher rates of absenteeism and lower workplace efficiency, leading to billions more in lost economic output, impacting employers and public health budgets. One widely cited analysis estimated the combined cost of physical inactivity, obesity, and overweight exceed $41 billion annually when factoring in healthcare, workers’ compensation, and lost productivity.

The Economic Benefits of Physical Activity

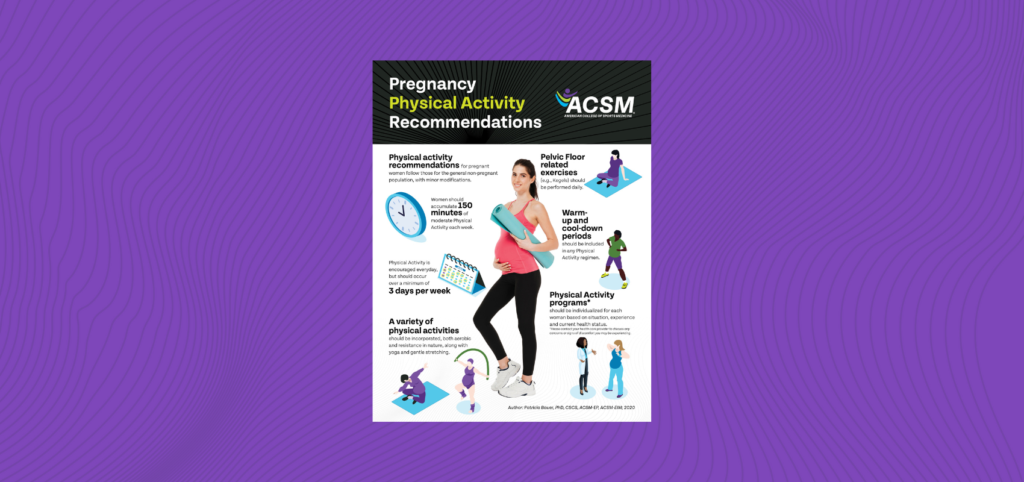

Promoting regular PA is one of the most cost-effective strategies for preventing chronic disease and improving overall health. Meeting the recommended PA guidelines can reduce the risk of over 25 chronic conditions, resulting in substantial health care savings over time. An active population is also more productive, with a higher workforce participation, reduced disability, and greater economic output.

The Economic Value of the Built Environment

Investing in infrastructure that supports PA is not only a health intervention, but also an economic development strategy. Parks, recreation facilities and active transportation infrastructure offer impactful economic returns. Among the top economic indicators are walkability scores, residential vacancies, housing affordability, property tax revenue, retail sales per square foot, the number of small businesses, vehicle miles traveled per capita, employment levels, air quality, and life expectancy. However, key metrics positively influenced by environments designed for activity are walkability, housing affordability, employment, air quality, and retail performance.

Walkable, bikeable communities with accessible parks and transit options experience increases in property values, retail sales, and tax revenues. For example, Safe Routes to School programs reduce car trips, improve safety, lower transportation costs, and even enhance academic performance and school attendance. These indicators help policymakers and community leaders measure and communicate the broad economic impact of creating more activity-friendly environments.

Advocating for Investment

Despite compelling evidence, PA programs and infrastructure remain chronically underfunded. For instance, a Smart Growth America report found that streets redesigned for pedestrians and cyclists saw a significant increase in business revenue and a decrease in commercial vacancy rates. Similarly, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has linked smart growth design to increased real estate value, economic resilience, and municipal savings (EPA, 2012). Public parks also generate measurable economic value. According to the Trust for Public Land (2020), every $1 invested in parks yields as much as $4 in return through increased tourism, higher property values, and reduced health costs.

The National Physical Activity Plan (NPAP) emphasizes the need for sustained funding at the federal, state and local levels, emphasizing that every dollar invested in active community design and programming produces measurable paybacks through healthier lives, higher productivity and stronger economies. The NPAP also provides strategies, tactics and objectives across ten societal sectors including Transportation, Land Use, and Community Design that can support public health professionals, advocates, and ACSM members in building a strong case for investment.

Key actions include:

- Advocating for increased federal, state, and local funding for parks, trails, and active transportation systems.

- Supporting initiatives that prioritize equitable access to PA opportunities in underserved communities.

- Partnering with economic development organizations to highlight the return on investment from PA friendly design.

- Using validated economic indicators to evaluate and communicate the impact of PA interventions.

Conclusion

The costs of physical inactivity are significant, but they are preventable. By investing in environments that encourage and support PA, communities can reduce healthcare costs, stimulate economic growth, and enhance quality of life for residents. PA is not just good for health; it is good economics. The time is now to move from evidence to action and fund the future of active living.