In my dual role as a mental performance specialist and researcher, I spend a lot of time in collegiate weight rooms, training rooms, and team meetings. One pattern is hard to ignore: we plan physical development with surgical precision, but we often assume mental toughness will “take care of itself.” Strength, power, GPS loads, sleep, and recovery are tracked. Mental toughness is expected. The last few years (through the COVID era and beyond) have exposed how costly that assumption can be. Collegiate athletes are navigating condensed schedules, public scrutiny, social media, NIL pressures, and lingering academic and psychosocial stressors. Some recent global events, such as the Paris Olympics, have underscored that high-performance systems can and should treat athletes’ psychological functioning as essential, not optional. We now have a growing body of evidence (and a lot of practical experience) showing that mental toughness is trainable, not just a personality trait some athletes are born with and others are not.

What Do We Really Mean by “Mental Toughness”?

In practice, when coaches and practitioners say, “mental toughness,” they often include a family of ideas: resilience, grit, composure, confidence under pressure, and the ability to bounce back from mistakes. As researchers, we know these are not the same construct. As practitioners, we know that people don’t draw that line; and that’s okay, as long as we’re clear on the goal: helping athletes consistently execute their skills under stress without sacrificing their well-being. Thus, we can use “mental toughness” as the umbrella term, while recognizing that different programs may emphasize slightly different components under that label.

What Comprises Modern Mental Toughness Training?

Across campuses, the most impactful work I have seen and studied shares three characteristics: brief, embedded, and ecologically valid.

1. Brief and integrated into existing workflows

In one six-session mental skills course with Division I athletes, relatively short sessions were enough to improve coping skills and mental toughness, with athletes reporting very high satisfaction and maintaining some gains months later. These sessions were scheduled around normal training demands, not in competition with them. For coaches and support staff, this is a key point: mental toughness training is not necessarily adding another hour to an already overloaded schedule.

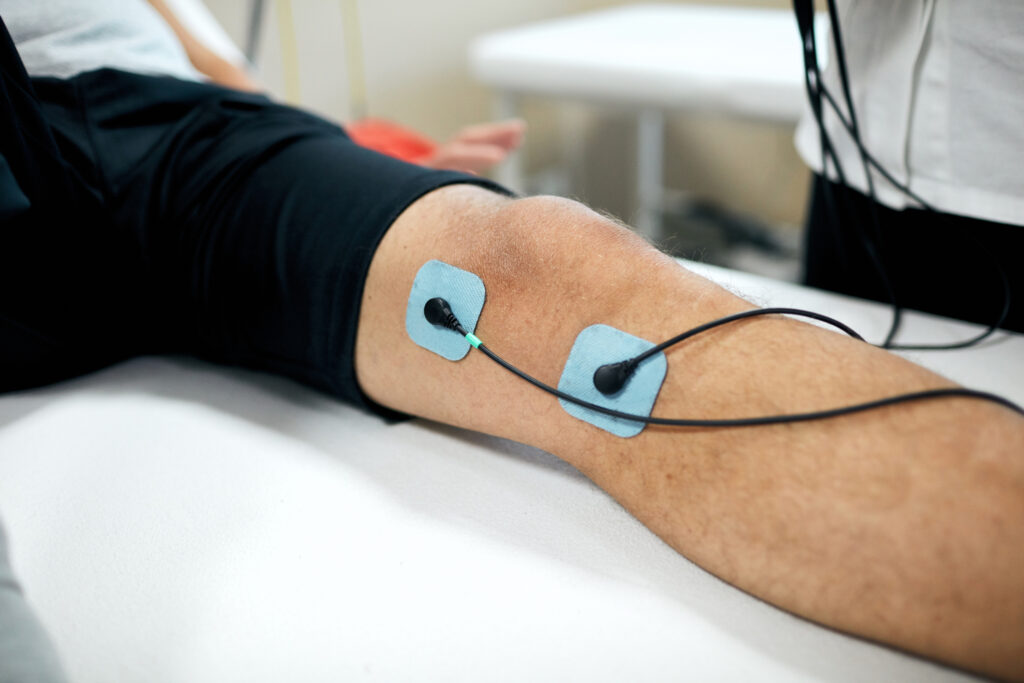

2. Embedded in strength and conditioning and practice

In collaborative work with strength and conditioning coaches, we’ve used pressure training to deliberately manipulate constraints (time, score, consequences) inside normal S&C sessions. Recent data from a Division I women’s team showed that pre-session mental toughness scores predicted performance during these pressure sessions, and that pressure training itself significantly increased athletes’ mental toughness over time (1). This is mental toughness training delivered in a language strength & conditioning coaches already speak: sets, reps, standards, and consequences.

3. Grounded in emotion regulation and self-compassion

Mental toughness is not just “push harder.” Athletes also need tools to recover psychologically from mistakes, injuries, and role changes. Self-compassion–based interventions have shown that teaching athletes to respond to failure with balanced, non-catastrophic self-talk can reduce self-criticism, depression, anxiety, and stress while improving perceived performance. Our own work with student athletes has similarly found that mental toughness and self-compassion are not opposites; they can co-exist and even reinforce each other.

Do Brief Mental Toughness Interventions Work?

Several studies now support what many practitioners are experiencing in the field:

- Resilience-focused programs (often framed as mental toughness by teams) for college student-athletes are associated with better coping, problem-solving, and stress management, particularly for first-year athletes navigating the transition to campus.

- Short-format mental skills training improves coping skills and mental toughness, with some effects maintained at follow-up.

- Self-compassion programs reduce distress and are perceived by athletes as directly helpful for performance.

- Pressure training in S&C appears to be a practical vehicle for both testing and enhancing mental toughness under realistic, sport-relevant stress.

Across these interventions, a common theme emerges. Well-designed micro-interventions (5–15 minutes), delivered consistently and embedded into training, can meaningfully shift how athletes think, feel, and respond under pressure.

What Comes Next?

Perhaps the next step is moving from isolated “mental toughness talks” to systems that integrate mental performance and mental health. Athletic trainers, strength coaches, and sport coaches share a common language around mental toughness and how they want it to manifest behaviorally. Screenings can be very useful, particularly when athletes may benefit from targeted mental toughness work or referral. Additionally, clear pathways between performance-focused services and clinical/behavioral health are needed, so athletes are not left to navigate siloed care. When universities prioritize these steps, mental toughness training stops being “extra.” It instead becomes part of how programs develop durable athletes and healthy humans.

Whether you work in the lab, on the field, or in the clinic, a few practical questions might guide your next steps:

- Where in your existing routines could a 5-minute mental toughness skill be embedded?

- How might you talk about mental toughness in ways that are meaningful to both coaches and clinicians, even if using slightly different language (resilience, grit, coping)?

- Who on your campus is already doing this work; and how can you partner with them?

Collegiate athletes may or may not have Olympic-level resources, but they can absolutely have an Olympic-level philosophy: performance and well-being are not competing goals. Mental toughness (however labeled) is the bridge between them. And that bridge can be built, rep by rep, in the environments many of us already influence.

Andreas Stamatis, PhD, is an associate professor, program director, and research fellow of mental performance & translational research in the Department of Health & Sport Sciences at the University of Louisville (UofL). He also serves as a Mental Performance Specialist with UofL Health and Louisville Athletics. He is a Fellow of the American College of Sports Medicine.